I was playing Minecraft the other night (on one of the few servers that the Bedrock gods have allowed us) and got myself an error message. One of those on a dirt block backdrop with white text telling me about a packet error. All the sound was cut. The button to dismiss the message wasn’t working. It glowed to indicate my input but no noise could be heard. I kept pressing it.

Nothing.

Eventually it just disappeared, not even kicking me out the game. It came and went. I soon forgot all about it and went back to playing, but it reminded me of a little theory I have. When it comes to breaking immersion, videogames have the most potential to make that concept terrifying. It’s not just with technical disbelief breaks like error messages and anti-piracy screens, but fourth-wall breaks from within a game can be used for great scares. In a medium that puts you in the driver’s seat, a sharp pull back into reality hits with far more momentum than it would in a show or film. From creepy error messages to file-reading villains to the game calling you out for your decisions, nothing does this brand of horror better than videogames.

An Irregularity Has Been Detected

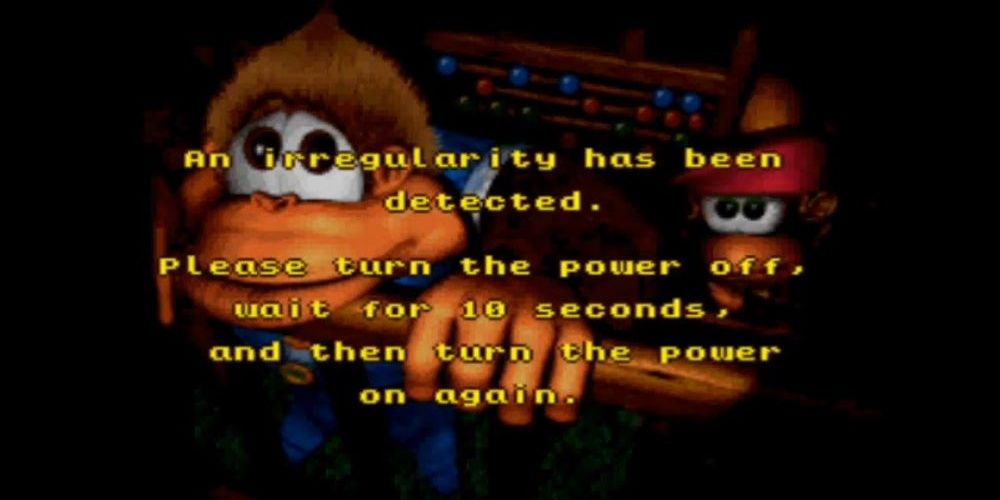

Let’s start out with those messages I mentioned before, because though Minecraft itself can be pretty creepy sometimes, the horror factor of these things is no isolated incident. Anti-piracy screens have blown up online, with many making fake versions of these messages as a new form of internet horror. Too many have an eyeless Mario flapping his gums and calling you a criminal, but some capture the subtle quality of real anti-piracy screens. For one of these real examples, just look at Donkey Kong Country 3.

Two saddened apes within some sort of black void, as if the background is hiding a secret behind low brightness, while plain yellow text talks about an “irregularity” being detected, like some sort of SCP has gotten loose. Anti-piracy screens like this lay the foundation for what’s scary about games breaking the fourth wall. Not only do they break the immersion, they’re accusing you of doing something wrong, regardless of how intentional that may be. This hits hard in games because they’re about agency; the player is far more involved in a game than they are with any other media. Thanks to that, you’re more likely to think that you’ve done something in-game to cause the screen.

This foundation is near and dear to the heart of fourth-wall breaking horror in games—something breaking the barrier between fiction and reality to acknowledge the player and potentially manipulate their experience (something most other media cannot do in real time). This has been adapted for intentional horror in games by playing on the idea of a self-aware entity recognizing the player’s actions and deciding to enact consequences.

You Like Castlevania, Don’t You?

While it’s not a horror game, Metal Gear Solid’s Psycho Mantis is probably the most well-known ancestor to modern fourth-wall breaks for horror. Mantis not only interrogates your tastes in games but judges you based on how often you save, calling you reckless if you don’t save often. He then meddles with your controller, forcing you to plug it into a different port. His messing with your hardware can freak you out because, like with those error screens, it breaks the safety of being immersed in a fictional world. He’s not coming for your character; he’s coming for you. It’s similar to films like Ghostwatch or The Blair Witch Project that are framed as if they really happened, only in this medium, the game can react to your decisions and act on that threat towards you.

Not only do they break the immersion, they’re accusing you of doing something wrong, regardless of how intentional that may be.

Perhaps the most famous example of taking all of this to its natural extreme is the much acclaimed Doki Doki Literature Club, an indie horror game that starts out as an innocent dating simulator but goes off the rails in its second act. Characters break down into creepypasta-edit versions of themselves, dialogue boxes glitch, and the game messes with files on your computer. An entity in the game, Monika, holds you (the player) captive in a pocket reality at the end of the game. Even closing out the title will boot you back to her. The only way to end the game is to delete her character data by delving into the game’s files. DDLC sucks you in with the first half before scaring you straight later, with your uniformed choices potentially leading to even greater strife within this glitched purgatory.

I couldn’t be happier to see this new trend of games that reach out of the screen to give you a good scare. Not only are more games utilizing ARG elements and forcing you to use resources from outside its bounds, they’re also letting you know that someone or something within the fiction is seeing what you’re doing and has the power to interfere.